Designing for Freedom, Part 2

This week, I want to continue to share how we designed Sunnyside, my last micro-school, with the following values in mind: freedom, creativity, and growth (check out our vision and mission here). While these three qualities are crucial to inspiring motivation in anyone, for twice-exceptional children, it’s central to their well-being. And for BIPOC twice-exceptional children, it’s paramount to their survival.

Racism—the unfounded belief that whiteness is supreme over all other races and ethnic identities—exists on the structural, curricular, and interpersonal level of conventional school (Kohli, et. al. 2017). In practice, racism in schools looks like psychological and sometimes physical violence directed towards BIPOC students to a disproportional degree when compared to white students. We’ve seen viral videos of Black children assaulted by school officials and/or experienced it or witnessed it ourselves. We know that Black children are more likely to be suspended or expelled from school than their white counterparts. Add all of this to the stigma and lack of understanding about what it means to be twice-exceptional, and it’s not hard to imagine some disturbing scenarios.

Dr. Joy Lawson Davis, a pioneer in the field of gifted education, is known for highlighting the need for increased equity in gifted education. She uses the term “3e” when discussing twice-exceptional Black and children of color. In her paper, “Being 3e, A New Look at Culturally Diverse Gifted Learners with Exceptional Conditions,” Davis shares, “The 3e label signifies three exceptional conditions: being culturally diverse members of a socially oppressed group; being gifted or having high potential; and simultaneously being LD or having another disabling condition (such as dyslexia)” (Davis & Robinson, 2018).

Sunnyside was designed with liberation in mind. I want all students everywhere to be free from imposed limitations on their drive and self-expression. As an anti-racist educator, it’s my duty to ensure that there’s space for all identities within the micro-schools I design and that the micro-school strives to be anti-racist on a structural, curricular, and interpersonal level. Cognitive freedom is intertwined with cultural freedom. To do justice to them both, we must affirm the identities of our students through word and deed.

Within Sunnyside’s structure, this looked like intentional diversity in our enrollment efforts. I’m not shy about stating that I’ve favored the enrollment of BIPOC students in order to create racial and cultural balance in the classroom.

The accessibility of the program was also considered when partnering with homeschool charters. Many offer learning stipends for enrolled children that can be used for programs like the ones I design.

In the classroom, anti-racist design looks like overtly teaching children about the historic and modern struggle for freedom as a content pillar within the curriculum and taking every opportunity to spotlight the achievements of underrepresented groups of people like Black and Latinx, LGBTQIA+, and women scholars.

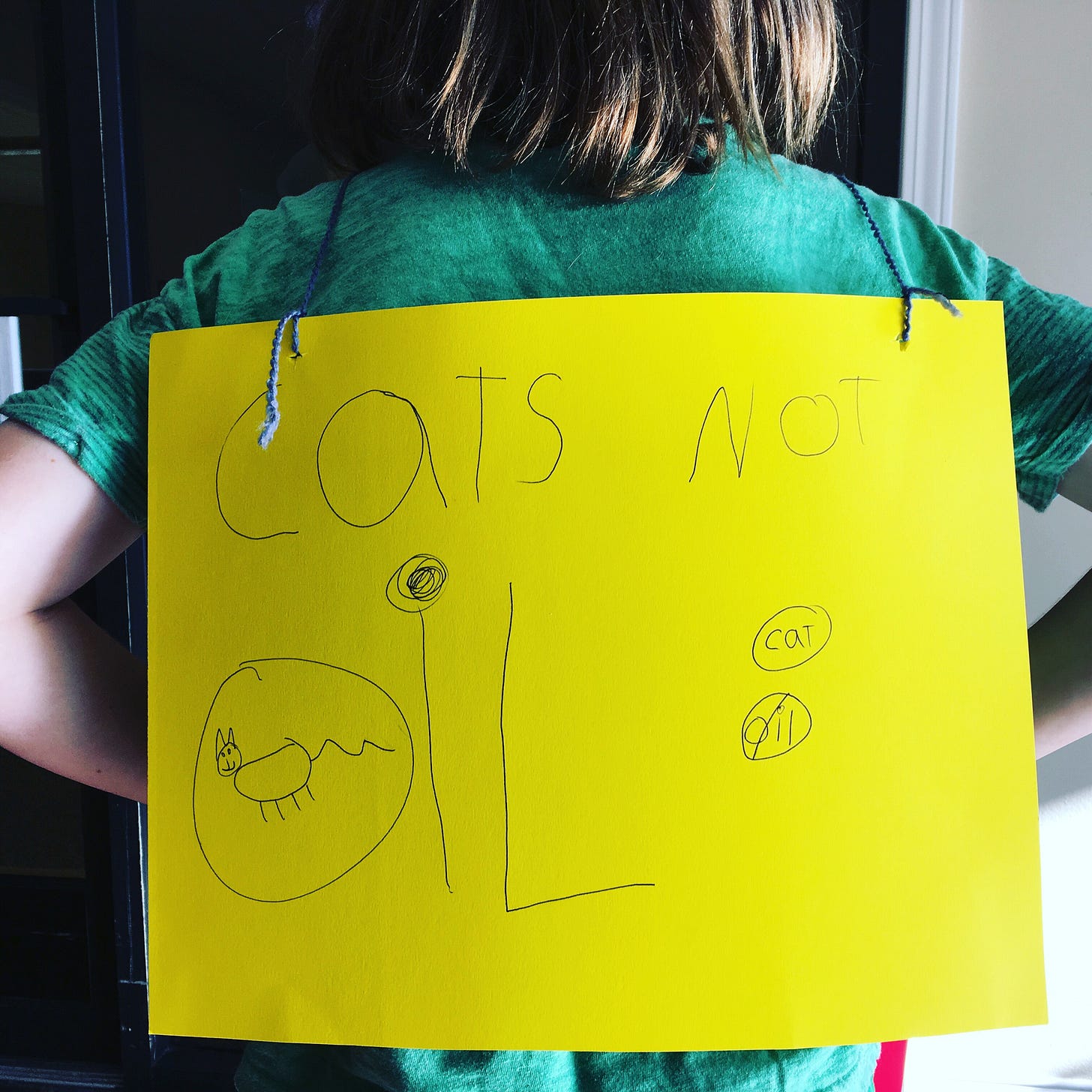

For example, when studying the difference between animal and plant cells, we learned about Henrietta Lacks and her non-consensual contribution to cancer research for the profits of predominantly white medical institutions. During our unit on the solar system, we discussed the way in which the Mayans were tracking the movement of the inner planets long before Copernicus. Quite radically, a Sunnyside educator originally from Colombia taught a gender-neutral form of Spanish to our students (part of his Master’s thesis). This praxis extended to the natural world as well, including education about the climate crisis and animal rights, as when we participated as a group in the Youth Climate Strike in Oakland in 2019.

Sunnyside students were taught about how the world worked while also being empowered to make the world a better place. While the debate rages on about the appropriateness of exposing children to the realities of our world, I’m here to report that leveling with kids about what’s real contributes to their overall well-being. It serves as powerful and authentic social and emotional learning. Kids know the world is in crisis—when we pretend that it’s not, we only contribute to their dysregulation and anxiety.

One student’s protest sign from the 2019 Climate Strike 🐱 🚫 ⛽️

To support our students, Sunnyside educators were offered high-quality professional development about implicit bias and anti-racist practices in the classroom. Race, identity, and inclusion were near daily topics of discussion, all in service toward making Sunnyside a more peaceful, free, and loving learning environment.

Living out the value of freedom in an educational setting means teaching what it means to be free and how to wield freedom responsibly and for the betterment of the world. It means explicitly discussing the imbalance of power and privilege that exists on every level of modern existence. It’s my experience that children understand these issues implicitly, as their rights are rarely considered or planned for. They appreciate the opportunity to consider and unpack what’s going on in the world with people who care for them. These actions and conversations do not have to be fraught; the matter-of-fact manner in which we introduced and maintained them was the same as the matter-of-fact way that I broke them down in the paragraphs above.

There is freedom in transparency. In fact, it cannot exist without it.

Next week we’ll unpack Sunnyside’s values of creativity and growth and how both relate back to my series on the magic of gradeless classrooms (check out those posts here and here).

Until then,

Jade

P.S. I was a guest on

podcast a few weeks ago, and the episode was released last week. In it, I talk about various cognitive types and ideas about how to best provide for them educationally.References

Kohli, R., Pizarro, M., & Nevárez, A. (2017). The “new racism” of K–12 schools: Centering critical research on racism. Review of Research in Education, 41(1), 182– 202. https://doi.org/10.3102/0091732x16686949

Davis, J. L., & Robinson, S. A. (2018). Being 3e, a new look at culturally diverse gifted Learners with exceptional conditions. Oxford Scholarship Online. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780190645472.003.0017